Introducing Product Variants: tracking product changes over time

Have you noticed that food products actually change? These can be permanent changes, or slightly different formulations sold in different places, or even seasonal, cyclical and subtle changes.

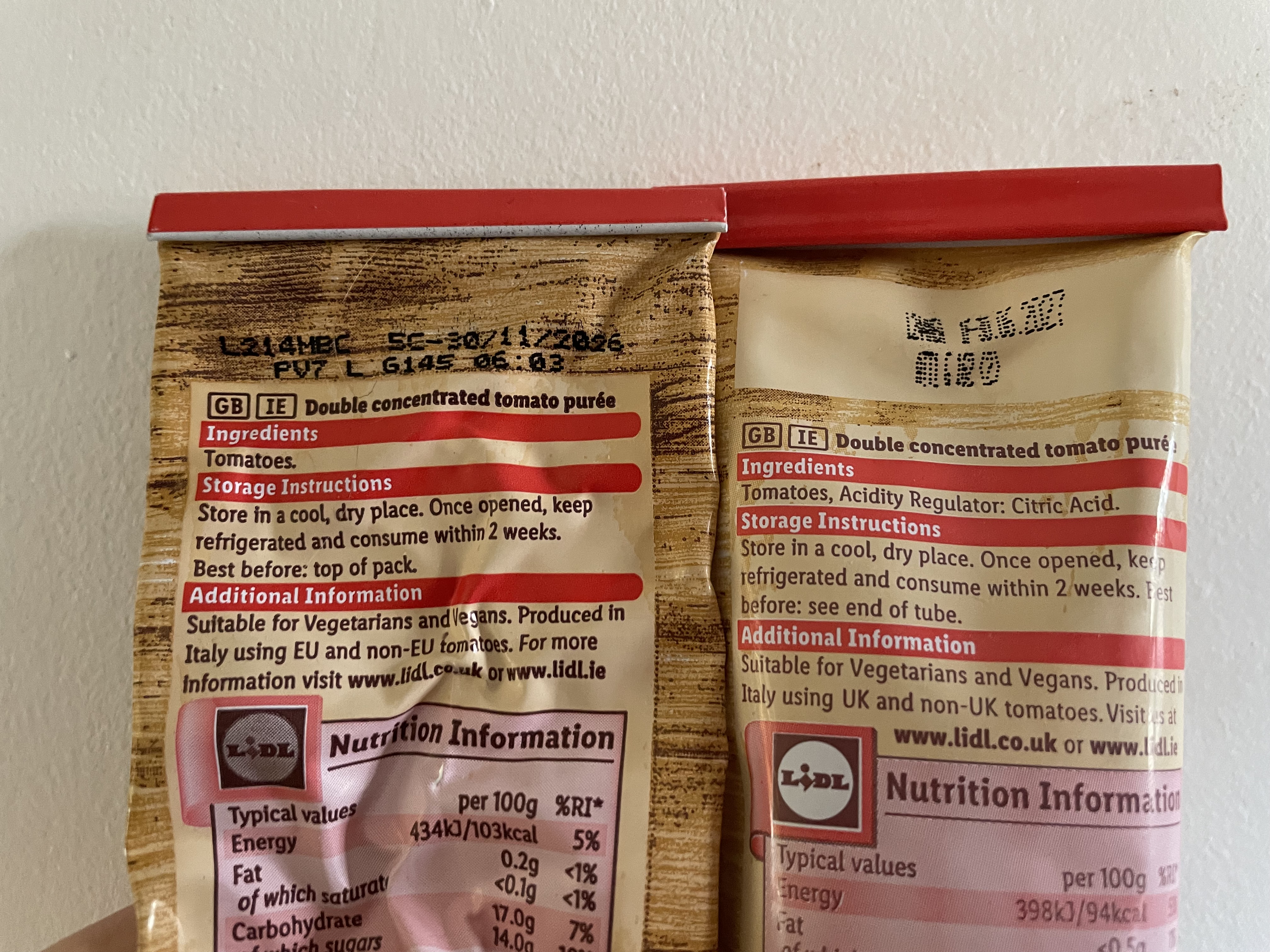

This is an example that I stumbled upon while shopping:

The two tomato purées are essentially the same product: same branding, same graphics, same barcode. They were bought at different times. The one on the left is an empty one I had at home, the one on the right was one I just purchased. Here’s a picture of both full tubes for reference.

The two tubes are essentially (numbers for 100g):

| Left | Right | |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients | Tomatoes | Tomatoes, Citric Acid |

| Energy | 103kcal | 94kcal |

| Fat | 0.2g | <0.5g |

| of which saturates | <0.1g | 0g |

| Carbohydrate | 17g | 17g |

| of which sugars | 14g | 17g |

| Fibre | 4g | 2.2g |

| Protein | 4.9g | 4.5g |

| Salt | 0.10g | 0.10g |

There is another small difference in that the total weight (the “200g” text) and the recycling symbols swap sides between one variant and the other.

The energy, sugars, fibre, and protein amounts are different. The negligible amount of fat and saturates is 0.5g or less for food labelling (Department of Health, 2017). Since both fat and saturates are under the negligible amount threshold, both labels can mean the same thing.

Looking at this particular tomato purée on OpenFoodFacts (link via the Web Archive since OpenFoodFacts data might change) we can see that the page aims to present a single product variant but, in fact shows pictures depicting different variants. Look at the image of the nutritional values, and then look lower down at the picture that has both nutritional values and ingredients.

I have noticed that the same canned chickpeas, under the same branding and barcode, can be either chickpeas and water, or rehydrated dried chickpeas and water, or sometimes may include an antioxidant.

Many products change over time, either in their nutritional values or ingredients. Sometimes these changes come with a “new” tag on the label, but oftentimes the changes are silent or unannounced.

Products can vary in different countries or regions. Products might vary based on the season or availability and price of raw ingredients.

Why is this important?

Knowing about product variants and keeping track of them is important for a few reasons.

Tracking apps typically only store one variant of a product. So it might look like it’s the right one but actually the one you have and the one the app knows about may have different ingredients and nutritional values. Avoiding ultra-processed foods or certain ingredients becomes harder. Food intake tracking becomes less accurate without noticing.

If a product has one variant with additives, and another variant that appears simpler, this pattern suggests the product is industrially engineered and likely ultra-processed overall. However looking at the variant with simple ingredients alone might not put the product in the ultra-processed category.

Keeping a history of product variants is also an important and interesting way to look at trends in the food industry.

Small note on barcodes

In apps, websites, and at checkout counters, food items are identified by their barcode. The barcode is a great tool for telling different products apart at the checkout counter, but it is not designed to identify unique product formulations. More than one product variant can have the same barcode. It is normal for products not to change their barcodes when changes are made to ingredients, nutritional values, or even packaging, graphics, or branding.

Sometimes even totally different products use the same barcode, although this is less of an issue since they can easily be told apart.

Also keep in mind that food items don’t need barcodes. Does your local real bread barkey use barcodes?

Product variants and ultra-processing

If you want to avoid ultra-processed foods, all of the products mentioned on this page are fine (NOVA 3), however if you mean to only buy the simplest variant, you have to be careful. And even though the examples used in this article don’t change NOVA group, products can definitely have variants in more than one group when looking at ingredients alone.

The history of the product might tell us a story that can contribute to the NOVA classification or at least how we look at certain items.

As an example, think of a product like an almond milk. Let’s say this particular product has only have a few simple ingredients and it is in NOVA group 3. Later it is reformulated, and the new variant has emulsifiers and gums. The new variant is in NOVA group 4 (UPF).

Another example where the opposite happens. Let’s assume a box of cereals that has among a few simple ingredients, some emulsifiers and gums. It is in NOVA group 4, ultra-processed. Later it is reformulated, and the new variant has a simple ingredient list without additives. By ingredients only, the new variant belongs to NOVA group 3.

The question we ask is: do the processed (NOVA 3) variants of these two products belong to NOVA group 3? Or should they be classified as NOVA group 4, ultra-processed, because ultra-processed variants exist in the market? We argue that all the variants of these products belong to the NOVA group 4, ultra-processed foods, because:

- The two variants are likely identical or very similar in graphics, branding and benefit from the same marketing campaigns. The differences on the product will be negligible except for the ingredients list and nutritional table. This makes choosing to avoid ultra-processed foods very difficult for the consumer.

- Formulation engineering signals ultra-processing by design. Products and processes can be optimised for a simple ingredients list just like they can be optimised for other factors like shelf life or texture (New Ingredients, New Processes: Managing Established Risks, 2024).

- The product line normalises ultra-processed foods. It reinforces the idea that ultra-processed foods are acceptable or unavoidable.

- Lack of ultra-processing signals on the label (ie. additives) does not imply a product is not ultra-processed.

Tracking product variants

Tracking product variants over time is one of the key reasons we are building a new food scanning app, Spotted. Spotted is still under development but if you’d like to find receive development and find out when we release sign up to our mailing list here.

References

- Department of Health. (2017). Technical guidance on nutrition labelling. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/technical-guidance-on-nutrition-labelling

- New ingredients, new processes: managing established risks. (2024). Campden BRI. https://www.campdenbri.co.uk/white-papers/ingredients-processes-established-risks.php